Skip to the content

Conditions under apartheid in South Africa may not be widely known or understood. It meant separate and inferior public services, benches and building entrances for anyone who was not white (European). Writing for The Associated Press, Michelle Faul described life in apartheid South Africa: Train carriages for black people (Africans) and people of mixed race or other non-white ethnicity (colored) were “decrepit,” and while gas stations would sell fuel to non-white drivers, these drivers were not allowed to use the restrooms.

But that was certainly not the extent of it. Under this racist policy, the non-white population was stripped of citizenship, and any and all non-white political representation was abolished, thus depriving the majority of the population of having any voice in the government.

Under apartheid, the minority white population (4.5 million people) owned 87 percent of the property, while the majority non-white population (19 million people) owned the remaining 13 percent.

Additionally, non-whites were forced into bantustans, where water was hard to come by and sanitation almost unheard of. As a result, it is estimated that 15 million South Africans were without safe water and 20 million without sanitation. Meanwhile, the white majority had all the water they wanted, and sanitation was not a problem for them.

Deciding the race of an individual was hardly scientific. One test was to see if a pencil would stay in a person’s hair. If the pencil slid through, the person was considered white.

“Under such rules of apartheid, Chinese were classified colored despite their straight hair; Japanese were white,” Faul wrote. “Blacks who wanted to be reclassified as colored also could undergo the pencil test: if it fell out when you shook your head, you could be become colored.”

It was not unusual for families to be separated due to such tests, including the removal of children from their parents.

Violence against the non-white population was endemic. Random shootings by white police of non-whites, kidnapping of non-whites, despite having the necessary paperwork that identified them, and rampant torture were all part of life in apartheid South Africa.

Boycotting South African apartheid

This system of apartheid didn’t sit well with the international community. In 1962 the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 1761, which declared apartheid to be a violation of South Africa’s obligations under the UN Charter and a threat to international peace and security. Member states were asked to voluntarily boycott South Africa and break diplomatic relations. Though initially ignored by most nations, this action, along with the creation of the U.N. Special Committee Against Apartheid, greatly encouraged the growing civil society-based, international solidarity campaign.

An academic boycott, begun in 1965, empowered principled academics from around the world to refuse invitations to South Africa to lecture and to pass on collaborating on scholarly projects with South African academics.

Athletics are an important component of South African society, and the sports boycott, begun in 1961 with South Africa’s expulsion from FIFA, the international soccer governing body, proved effective. South Africa was excluded from many international rugby and cricket competitions, not to mention the 1964 Olympics. After nearly 50 countries threatened to boycott the 1970 Olympics in protest of possible involvement by South Africa, the country was expelled from the Games.

Starting from the mid-1980s, the European Community and Commonwealth countries imposed some trade and financial sanctions. In the United States, President Ronald Reagan opposed sanctions, but, to appease Congress, did agree to a limited ban on exports. (It must be remembered that the U.S., never at the forefront of human rights when power or economic strength may be compromised, considered Nelson Mandela, the longtime leader of efforts to overturn South African apartheid, a terrorist. Indeed, Mandela was on a “terrorism watch list” as late as 2008, decades after some semblance of democracy had been initiated in South Africa.)

Another major effort was the grassroots campaign to encourage institutional investors to withdraw all investment from countries based in South Africa. American university campuses became a focal point for such efforts.

Now and then

Apartheid in South Africa officially ended with the 1994 elections in which members of all races were allowed to vote.

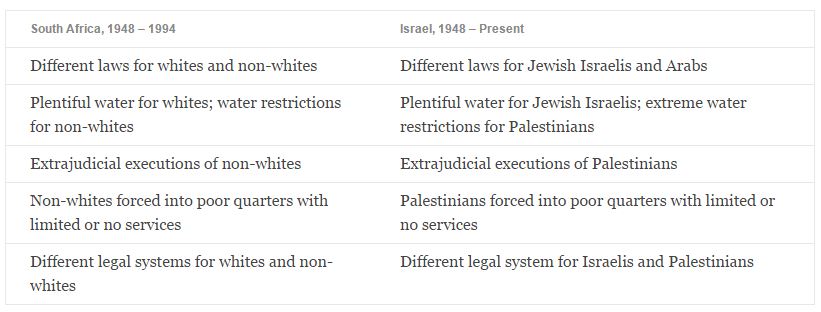

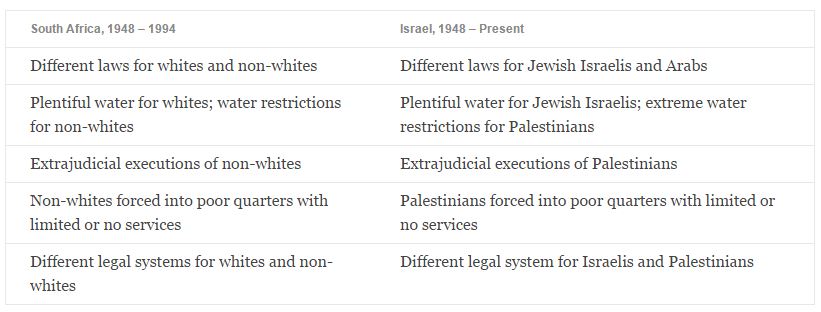

Yet the ugliness of apartheid still exists elsewhere, most notably in Israel. A few examples highlight the similarities of South African apartheid and Israeli apartheid:

One hates to sound cynical, but, as with so much in U.S. governance, it all seems to come down to money. Between April 1, 2009 and March 31, 2015, Israel lobbies contributed $12.6 million to U.S. senators for election, re-election and presidential campaigns. From April 13, 2013 to March 31, 2015, Israel lobbies contributed $4.3 million to members of the House of Representatives for election, re-election and presidential campaigns. A 2013 report indicates that, at that time, winning a senate seat in the U.S. cost about $10.5 million, while a seat in the House of Representatives cost about $1.7 million. It is much easier, certainly, to obtain a single contribution of tens, or perhaps hundreds, of thousands of dollars, than to collect that amount with donations of $5 or $10 from working people.

The impact of the Israel lobby on American politics is nothing new, though. In 1984, incumbent Sen. Charles Percy of Illinois was defeated for re-election by Paul Simon. Mr. Simon was tapped by the American Israel Political Affairs Committee to run against Mr. Percy, who had acknowledged not on

ly the existence of the Palestinians, but also that they had rights. This was untenable in a U.S. senator, and with backing from the powerful AIPAC, Mr. Percy was defeated. Congressional dissent from the AIPAC party line will not be tolerated.

At the recent AIPAC convention, GOP presidential candidate and Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, who, during the six-year period mentioned above received $100,354 from Israel lobbies, actually told his receptive audience that “Palestine has not existed since 1948.” This was perhaps the most extreme statement made to AIPAC audience by anyone seeking the U.S. presidency this year.

Money and fear fuel support for Israel

In February of 1986, Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme participated in “The Swedish People’s Parliament Against Apartheid,” during which he described apartheid as “this despicable, doomed system.” He was assassinated one week later. After Sweden officially recognized Palestine in 2014, Sweden’s foreign minister, Margot Wallström, received numerous death threats.

France and Belgium are two additional countries that seem, at least in some regards, favorable to Palestine, and there has been talk in both nations about recognition of Palestine. Some pundits note that it is, at best, an odd coincidence that each experienced a “terrorist” attack after making known their intentions about recognizing Palestine.

So it appears that money and fear play a significant role in global support for Israel, but that support is quickly fading, as more countries recognize Palestine and condemn Israel. Steps by the European Union requiring appropriate labeling of Israeli goods produced on occupied land; the increasing academic, economic and entertainment boycott of Israel; and even the U.S., Israel’s main financier, approval of the Iran nuclear agreement that Israel spent as much as $40 million opposing, all point to a major change in world opinion.

Frederick Douglass, who fled slavery and went on to become a leader in the abolitionist movement and American statesman, once said, “Power never concedes anything without a demand; it never has and it never will.” The world is now demanding that Israel surrender its power over Palestinians. Israel is resisting, as it has for decades, but as the weight of the demand increases, Israel will eventually bow beneath it.